History of Struggle and Survival

The Puyanawa, a Pano-speaking tribe, have historically lived along the banks of the Moa River in the Amazon region of Acre, Brazil. Their history has been marked by painful episodes during the rubber extraction boom in the twentieth century, where they faced violence, disease and exploitation. Like many other indigenous peoples, they were forced to work in deplorable conditions in the seringais (rubber extraction areas) and suffered the loss of their autonomy and territory.

First Contacts and Colonization

The first documented contact with the Puyanawa occurred in 1901, when rubber tappers began to invade their lands. The Puyanawa resisted and evaded the colonizers initially, but eventually some were captured and forced to join rubber mining activities. These early encounters were followed by a series of expeditions that resulted in the forced pacification and relocation of the tribe, profoundly altering their way of life.

Cultural Recovery and Land Demarcation

In recent decades, the Puyanawa have experienced a cultural renaissance, working hard to reclaim their native language and revitalize their traditions. This effort has coincided with the struggle for the official demarcation of their territory, a vital process to ensure the survival and future prosperity of the tribe.

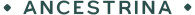

Unique Cultural Aspects

The Puyanawa are known for their rich facial tattoos, a traditional practice that symbolizes maturity and status within the community. In addition, they maintain unique rituals related to the handling of the dead, where the remains of the deceased are cooked and consumed in an act of mourning and celebration of the life of the deceased, believing that this helps to incorporate the qualities of the deceased into the living.

Current Challenges and the Way Forward

Despite having made significant progress in recovering their culture and securing their territory, the Puyanawa still face numerous challenges. Continued pressure from the timber and agricultural industry threatens their lands, and integration with the wider Brazilian society presents challenges to the preservation of their unique cultural identity. However, their resistance and resilience continue to be a source of inspiration and a call to action for the protection of indigenous rights in Brazil and around the world.

Explore more about your spiritual and ancestral well-being with Ancestrina. Visit our store to discover authentic products that connect you with ancestral traditions, or join our community to learn more and share your experiences. Your journey towards holistic well-being starts here! Click here to learn more and begin your journey with us.